We Must Dare to Show Human Suffering

Images of human suffering disturb and unsettle, but their power lies in their discomfort. When we shy away from depicting painful realities, whose comfort are we truly protecting?

A few years ago, an image of three-year-old Alan Kurdi, washed up on a Mediterranean beach, spread from a Turkish newspaper’s website to every corner of the globe. Captured by Turkish journalist Nilüfer Demir, the photograph reached iconic status perhaps faster than any before it. Yet its publication also drew criticism. The Finnish newspaper Turun Sanomat chose not to publish the image on the grounds that a comparable photo of a Finnish child ‘would never be published’.

Two-year-old Alan Kurdi, found lying face-down on a beach near the Turkish resort of Bodrum, was one of at least 12 Syrians who drowned while attempting to reach Greece. Photo: Nilüfer Demir

Images depicting human suffering from crisis zones and the world’s poorest regions repeatedly provoke debates about double standards in the media. Critics frequently argue that similar images of people from affluent countries would not be disseminated. They pose the rhetorical question: would you want a picture of your own child in such circumstances shared globally?

However, the premise of this criticism is flawed. It compares the plight of those in crisis zones directly with the middle-class experience in wealthy nations. While hunger and poverty can indeed occur anywhere, conditions and cultural attitudes significantly shape what people find humiliating or shameful to reveal publicly.

Discussing poverty is fundamentally different in Syria, where 90 per cent of the population live below the poverty line, than in Finland, where the equivalent figure hovers around 12 per cent.

Furthermore, individual experiences differ widely. It is imperative, therefore, to ask those directly involved whether they wish their stories told. Silencing those willing to share even harrowing experiences serves nobody. This problem also arises in Finland among marginalised communities, who are frequently unseen and unheard, even concerning issues that directly affect them.

Silencing those willing to share even harrowing experiences serves nobody.

When the Finnish railway company VR decided to remove benches popular among homeless people at Helsinki Central Station in autumn 2020, I went there to photograph the story. I encountered a man who, in the absence of benches, was sitting on the floor next to a radiator for warmth. He readily agreed to be photographed and explained how crucial indoor warmth was during winter.

Yet, the published story showed only the removed benches and quoted a VR project manager. Perhaps the real double standard lies in paternalistic attitudes preventing vulnerable people from making their own hardship visible. Are we genuinely protecting individuals who have not been consulted, assuming that showing their struggles would be too distressing? Or are we instead shielding that part of the public preferring to turn a blind eye to uncomfortable realities?

Of course, it matters profoundly how individuals are portrayed in photographs. A photographer wishing to give voice to their subjects must not only observe but also listen.

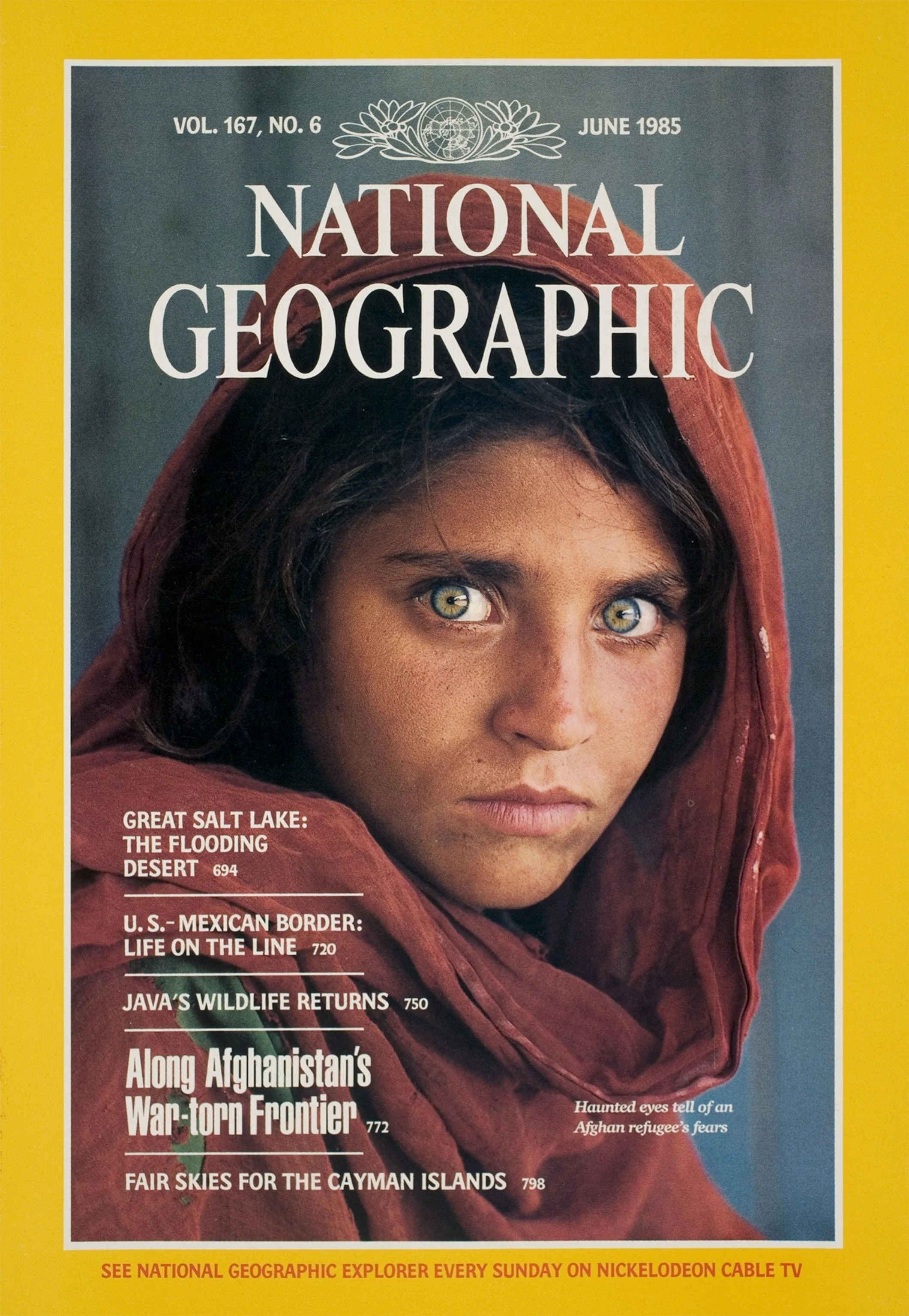

The history of photography—and no doubt its present—abounds with examples of photographers failing to listen. In 1984, photographer Steve McCurry famously captured the image of an ‘Afghan girl’ at Nasir Bagh refugee camp in Pakistan, without her consent.

Published on National Geographic’s cover under the caption ‘Haunted eyes tell of an Afghan refugee’s fears’, it took seventeen years before Sharbat Gula could tell the photographer her name and that her expression was not fear, but anger.

Steve McCurry’s unauthorised portrait of Sharbat Gula, known for years only as the ‘Afghan Girl’, became an icon of conflict photography even as her own voice went unheard.

Photography has the power to convey realities forcefully and shape public perception profoundly. Parties in the war in Ukraine clearly understand and exploit this power. War is horrifying, and photographs should truthfully reflect its horror. Yet, images depicting suffering risk becoming monotonous if they fail to portray a broader sense of life in crisis regions. Showing suffering should never become an end in itself.

Even amid crisis, life involves hope and occasionally joy, as seen in Giles Duley’s photos from the 2015 refugee crisis. Parents help children with homework, children keep playing, and hospital staff urgently tend gunshot wounds.

Ultimately, more important than showing how people die is depicting how they manage to survive.

Abdullah Kurdi, father of Alan Kurdi, told German newspaper Bild in 2016 that he was glad the photograph was published. He believed that seeing it helps people understand the world refugees are fleeing.

Aya being pushed in her wheelchair by her brother Mohamad. Her family fled from Idlib in March 2014 after their house was bombed. Photo: Giles Duley / UNHCR

I wrote this article before Russia launched its full‑scale invasion of Ukraine. It first appeared in Finnish in Journalisti, the trade magazine of the Union of Journalists in Finland, on 23 March 2022, under the title ‘Ihmisten kärsimys täytyy uskaltaa näyttää’.

Since the invasion began, debate over the publication of graphic images of suffering—particularly of the dead and the dying—has intensified. In Finland, some retailers even removed newspaper placards carrying such photographs. Yet war is shocking and brutal, and it must be portrayed as such in pictures and in words, even when it might cause distress for the readers.